A Mandatory Base Acre Update Divides Agriculture

Key Takeaways

- A mandatory base acre update would force farmers to update their farm’s base acres to reflect a more recent snapshot of their planting history. The economic effects are significant and are conservatively estimated to result in an overall loss of $2 billion to farmers and rural communities and economies due to a decline in farm program benefits during fiscal years 2024 to 2033.

- Few in agriculture benefit from a base acre update. A mandatory base acre update would create winners and losers among neighbors, crops, counties, and states, and most certainly would complicate efforts to successfully pass a new farm bill.

For more than two decades, and over the course of the last four farm bills, farm program payments have been based on a farm’s historical planted acreage, i.e., base acres, and not on actual plantings each year. Decoupling Agriculture Risk Coverage and Price Loss Coverage farm program payments prevents farmers from making planting decisions based on expected program payments. Instead, the current system ensures farmers evaluate only market supply and demand signals and expected returns per acre when determining which crops to plant each year.

Since production flexibility contracts were used to establish what we know now as base acres in the 2002 farm bill there have been several modifications to base acres. Specifically, the 2008 farm bill added base acres for pulse crops; the 2014 farm bill provided an opportunity to voluntarily reallocate base acres; the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 converted generic base acres into seed cotton base; and the 2018 farm bill temporarily removed base acres that were planted continuously to grass from 2009 to 2017. In the process of passing the last three farm bills, Congress has recognized the value of decoupled commodity program payments and refrained from making mandatory modifications to base acres that would adversely impact farm income, farm equity, farm real estate markets, and ultimately – the farm economy.

To provide perspective on the adverse impacts associated with a mandatory update to base acres, USDA individual farm-level information on planted acres, acres considered planted, and acres prevented from being planted was used to reestablish base acres by farm using average plantings from 2018 to 2022 -- i.e., eliminate all existing base acres and create new base acres by farm and by crop using average plantings from 2018 to 2022. The change in base acres was based on the difference between recently enrolled base acres and the reestablished base acres. Then, the economic costs or benefits associated with the change in base acres were calculated at the state, county, and crop level using average program payments by crop from the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) May 2023 baseline for USDA Mandatory Farm Programs.

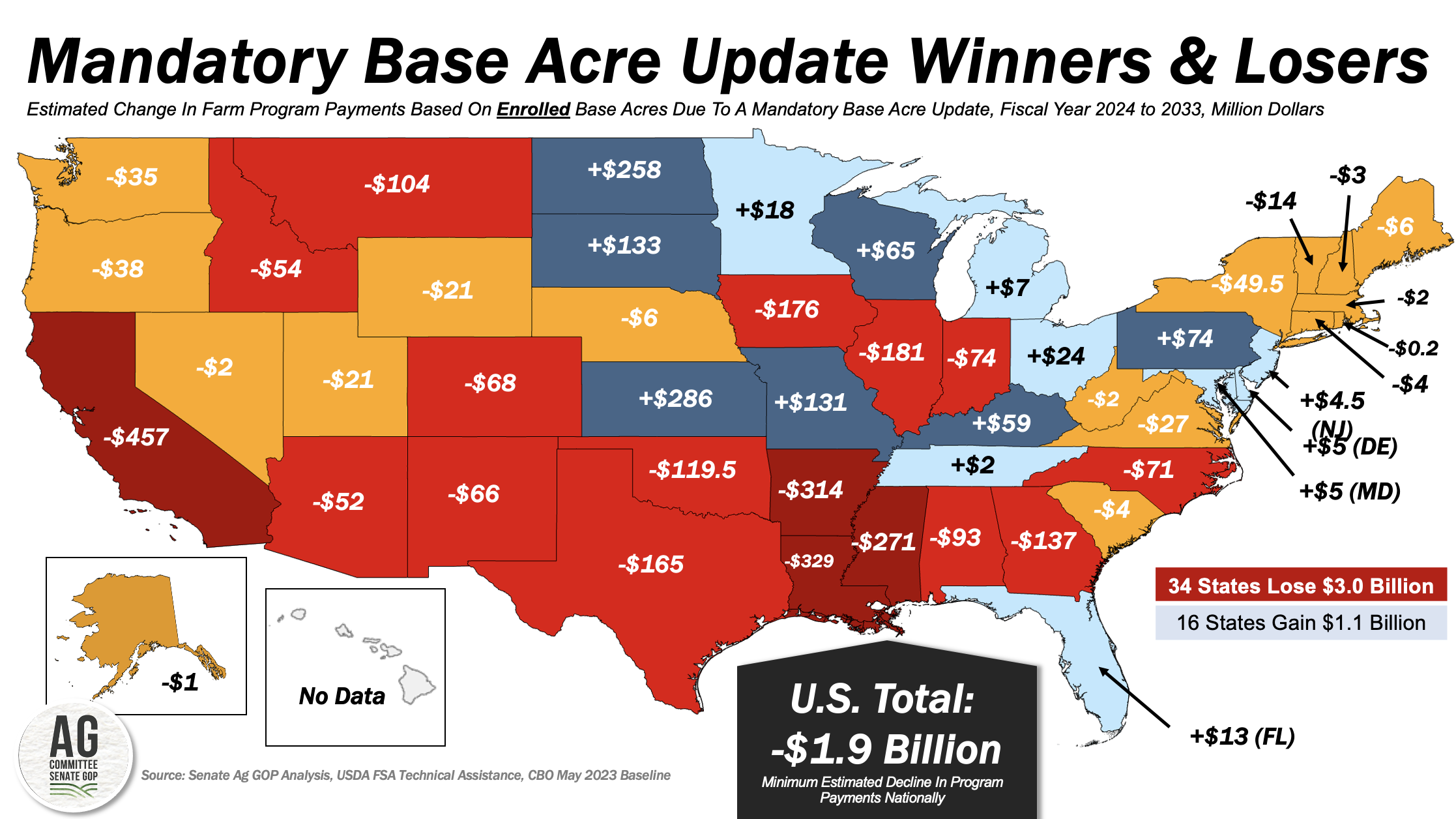

For the 2024 to 2033 fiscal years the economic costs associated with a proposed mandatory base acre update result in a projected decline in farm program payments of nearly $2 billion (Note: This is not an official score of a mandatory base acre update from CBO). This is largely due to significant shifts in commodity-by-commodity base-acre changes. For example, in Iowa and Illinois – the largest two corn-producing states in the U.S. – the economic impact is significant to farmers. Losing corn base and gaining soybean base results in a projected economic loss of $356 million from fiscal year 2024 to 2033. Similarly, in Georgia, the largest peanut-producing state, the decline in peanut base and increase in seed cotton base results in a projected net economic loss to farmers of $137 million from fiscal year 2024 to 2033. In total, there are 34 states that have a net negative economic impact associated with a mandatory base acre update totaling a projected $3 billion in lost assistance.

While most states will see lower program benefits in aggregate as a result of a mandatory base acre update, some states are estimated to receive net positive economic benefits. For example, in North Dakota and Kansas, both stalwarts in wheat production, the shift from wheat production into corn and soybean production has significant impacts during a mandatory base update as wheat base acres will be lost but replaced with corn and soybean base. The net combined effect in North Dakota and Kansas is a projected increase in farm program payments of $544 million given CBO’s projected payments per base acre during fiscal year 2024 to 2033. Across the U.S. there will be 16 states with a positive net expected benefit associated with a mandatory base acre update totaling $1.1 billion.

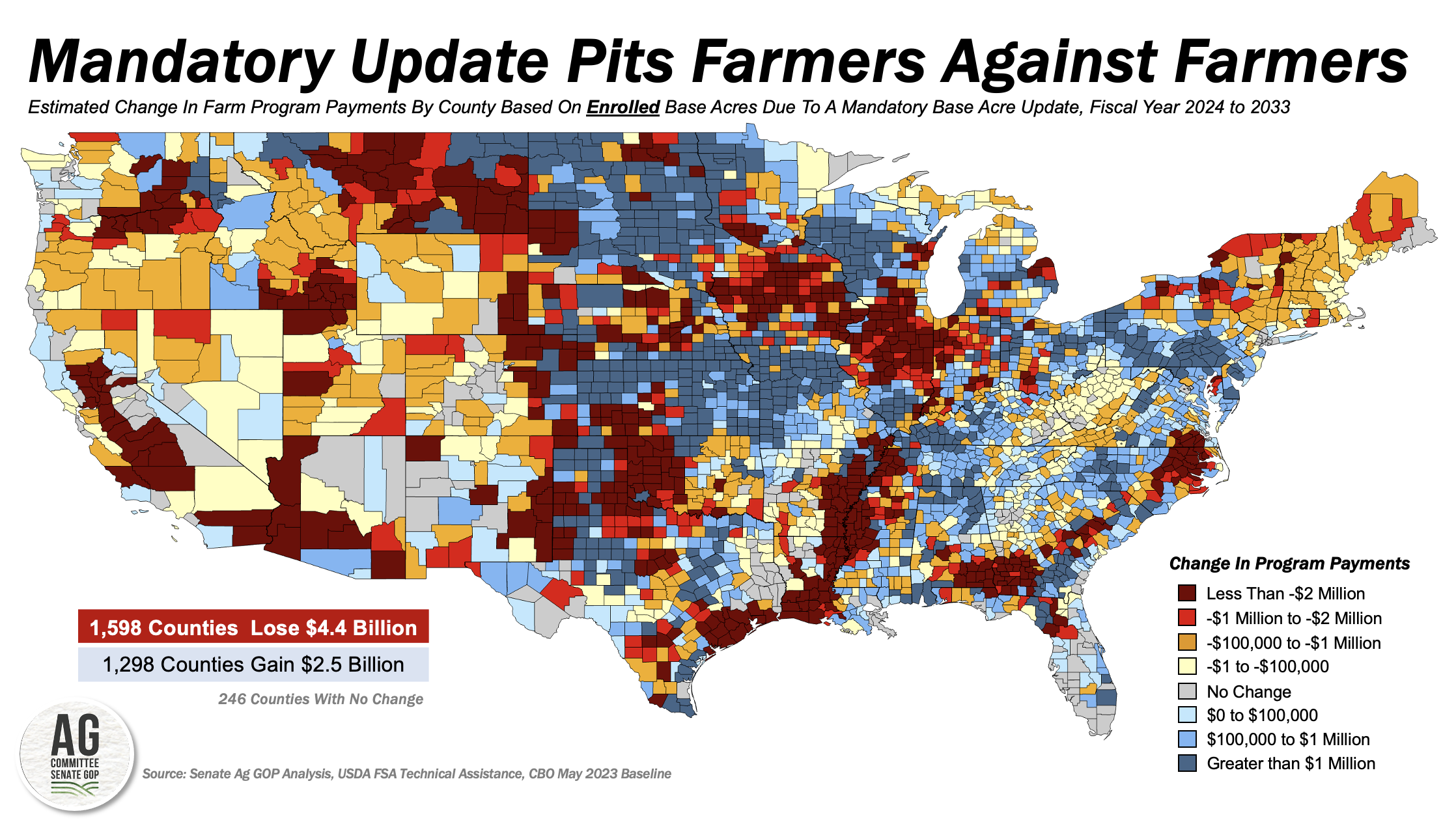

It is clear that a mandatory base acre will, in aggregate, create winners and losers in farm country by state and by commodity, but it also pits farmers against farmers. Some farmers may lose base entirely or end up with a new alignment of base acres that lowers their farm income and weakens asset values. Across the U.S. there are nearly 1,600 counties where a mandatory base acre update results in lower projected economic returns totaling $4.4 billion.

Other farmers may gain base acres on acres that historically were not in the production of covered commodities, e.g., pasture ground that is now in the production of corn and soybeans. In other instances, farmers may end up with a new alignment of base acres with higher expected program payments. For these farmers, the mandatory base acre update would increase farm income and farmland asset values. There are nearly 1,300 counties with higher net expected program benefits totaling $2.5 billion.

As evident in this analysis, and for good reason, Congress has ensured that any modifications to base acres were mostly voluntary in nature, as the gross negative economic effects associated with a mandatory base acre update is harmful to producers as it benefits some producers at the expense of many producers.

Instead of dividing agriculture, Congress has historically addressed base acres in a manner that benefits farmers by either adding or restoring base acres where needed or providing farmers an opportunity to reallocate their base. Under a voluntary base acre update farmers can re-proportion their base acres to meet their individual business needs – avoiding the need for those in Washington, D.C. to hand-pick winners and losers in agriculture.