The Truth Behind “Shrinkflation”

Let’s Take a Look at President Biden’s Latest Inflation Excuse

Key Takeaways

- In his latest effort to avoid responsibility for the historic inflation in food and grocery prices, President Biden tried to lay the blame at the feet of food companies-- accusing them of a practice called “shrinkflation” -- during his State of the Union Address. This follows a similar effort in 2021 to blame inflation on food processors. However, he will need to keep searching for a scapegoat as data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reveals that product downsizing played only a minor role in the rapid increase in food prices that occurred under this administration.

- As part of the process of collecting accurate data needed to estimate the Consumer Price Index, BLS economists not only monitor product prices, but they monitor product sizes. This allows BLS to ensure that product size changes associated with shrinkflation are accurately reflected in the CPI. BLS found the impact of shrinkflation was not significant – on average accounting for less than 2 percentage points of the overall price increases.

- The historic and persistent inflation that continues to plague the U.S. economy, and food prices in particular, is driven by trillions of dollars in federal spending championed by the president. Bidenomics overheated an economy recovering from COVID-19 supply chain disruptions and is chiefly responsible for the record-high food costs that continue to sap earnings from hardworking Americans.

Issue

Based on estimates from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, the inaptly-named Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, and the 2021 Thrifty Food Plan Re-evaluation combined to increase federal spending by trillions in fiscal years 2021 and 2022. At a time when the economy was still recovering from COVID-19 supply chain disruptions, this rapid and significant influx of funding overheated consumer demand and contributed to historic inflationary pressure across the entire U.S. economy. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine made matters worse by driving energy prices higher and reducing grain and oilseed supplies globally.

Led by food, transportation, energy, and housing costs, consumer prices have increased nearly 20% since January 2021. The cumulative impact of inflation over the last 37 months is the highest pace of inflation of any administration since President Carter was in office.

President Biden previously tried to downplay the impact of food and grocery price inflation on the financial well-being of U.S. households by inaccurately blaming concentration in the meat and poultry processing industry. This excuse failed to recognize the impact of labor shortages on meat and poultry companies.

Now, the administration is blaming food price inflation on another component of the supply chain -- this time accusing food companies of “shrinkflation.” President Biden raised this idea during the Super Bowl and most recently during the State of the Union address.

While shrinkflation, the practice of downsizing product size or quantity while keeping the nominal price unchanged, has occurred, unfortunately for the administration, its economists at the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) have revealed shrinkflation is not a significant culprit behind stubbornly high grocery prices. According to BLS: “while consumers may notice shrinkflation at the grocery store, it has a very small impact [on] the overall inflation picture they face.”

Bidenomics and Food Prices

Food price inflation, which includes food purchased at the grocery store and while dining out, peaked at 11.4% in the summer of 2022 and has increased by 21% since January 2021. Like overall inflation, food price inflation is the highest of any administration in over four decades.*

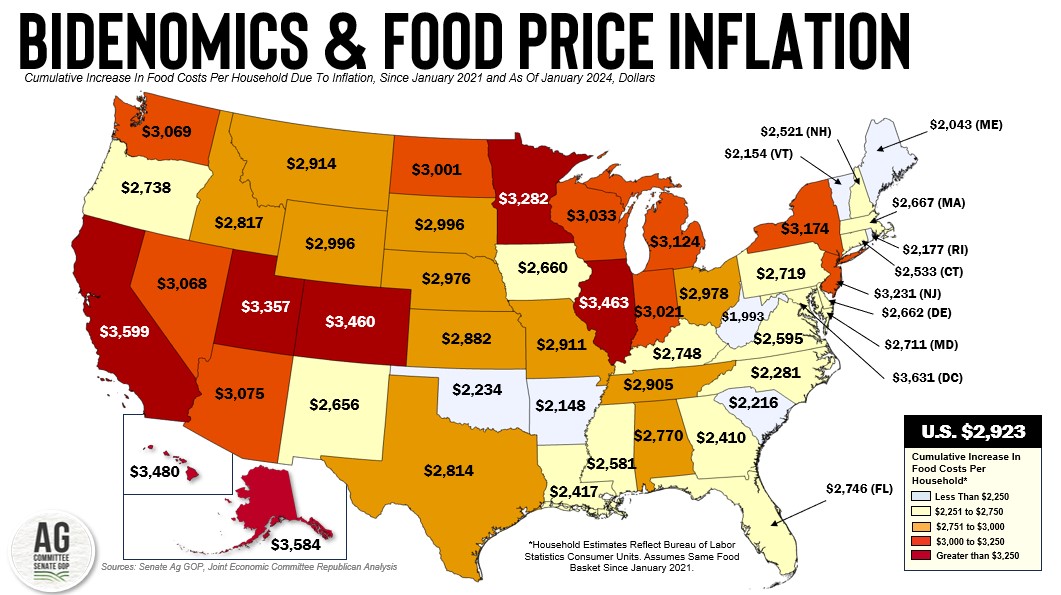

Republicans on the Joint Economic Committee have been monitoring the impact of inflation across multiple consumption segments through the State Inflation Tracker. According to their analysis, as of January 2024, American households would have to spend $140.16 more each month to maintain the same food basket purchased in January 2021 and cumulatively have spent more than $2,900 more on food than before this administration.** Across the U.S., the cumulative increase in food costs paid by households under this administration ranges from a low of nearly $2,000 in West Virginia to more than $3,000 in Alaska, California, Colorado, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Minnesota, and Utah.

“Shrinkflation” Is Not to Blame

As part of the process of collecting accurate data needed to estimate the Consumer Price Index (CPI) BLS economists not only monitor product prices, but they monitor product sizes. This allows BLS to ensure that product size changes, e.g., weight and volume changes associated with shrinkflation, are accurately reflected in the CPI.

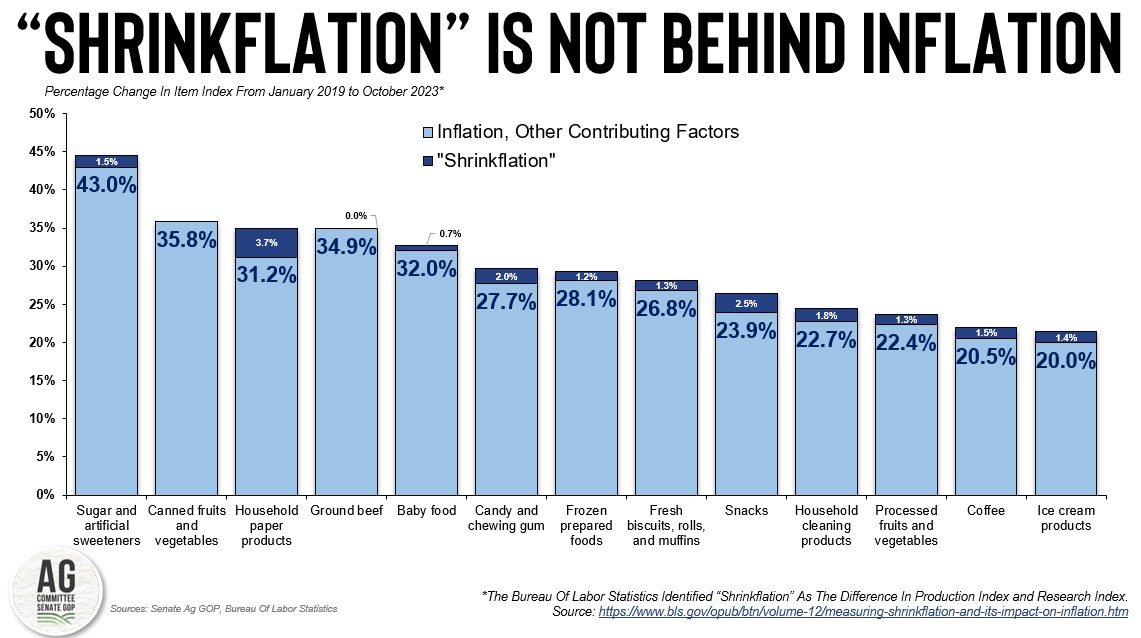

A recent analysis by BLS revealed that of the 26% increase in the price of snacks from January 2019 to October 2023, shrinkflation accounted for only 2.5 percentage points of the increase. Similarly, for ice cream products, which have experienced a 21% increase in price, the impact of downsizing accounts for only 1.4 percentage points of the total percentage change.

On average and across the food categories analyzed by BLS, the impact of shrinkflation was not significant – accounting for less than 2 percentage points of the overall price increases.

Conclusion

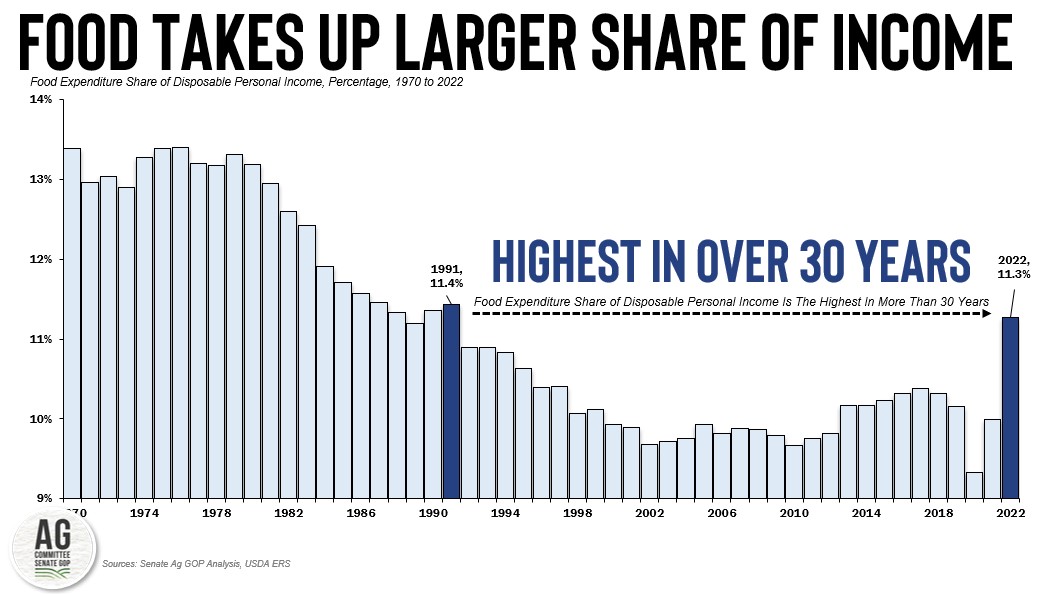

Throughout this administration, consumers have experienced increases in prices for beef and poultry products, milk and other dairy products, eggs, and staples such as flour, bread, and rice. In fact, according to USDA’s Economic Research Service, on average U.S. households spent nearly $16,000 on food in 2022, representing 11.3% of the household’s disposable income. At 11.3%, and driven by historic inflation, the household share of disposable income spent on food is the highest that it has been in more than 30 years (since 1991). Unfortunately for the administration, the large share of household income spent on food due to historic inflation in food costs is not driven by shrinkflation.

Farmers are not to blame either. The inflationary pressure consumers are experiencing in food costs and the grocery store does not directly translate one-to-one into higher farm-level prices or farm income. In the face of record-high food prices farmers received on average only 7.9 cents of each dollar spent on food in 2022.

Many links in the supply chain get food from American farmers to the kitchen table, but neither farmers nor food processors through higher commodity prices, concentration, or shrinkflation are to blame for higher food costs. Instead, too much federal spending by the administration overheated an economy still recovering from COVID-19 supply chain disruptions. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine further disrupted global energy and food supplies. Higher labor costs, higher energy, and higher transportation costs drove the costs of food service, food processing, and food distribution higher. Those are the real economics of food price inflation.

*During the first 37 months in office.

**To estimate the impact of food price inflation on household spending by state, the JEC Republicans used data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditures Survey, the Bureau of Economic Analysis Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index, and the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.